Traditional Islam and a tale of 2 reformations

by Dr. Mazeni Alwi

Ah love! Could thou and I with fate conspire

To grasp this sorry scheme of things entire

Would we not shatter it to bits

And remould it nearer to the heart’s desire!

(from the Rubaiyat by Omar Khayyam; translation by EJ Fitzgerald)

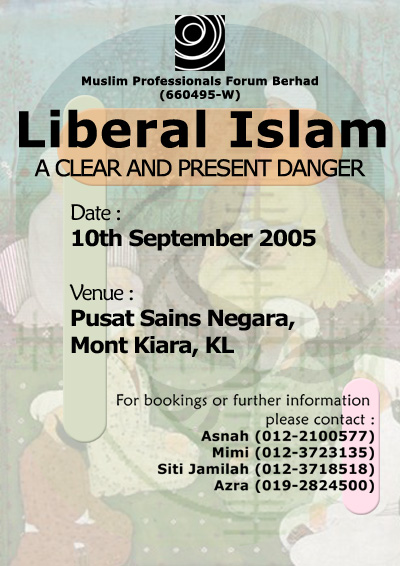

Writing in the Washington Post last month, Salman Rushdie has lent his weight to the rousing chorus that calls for the “reformation” of Islam in the wake of 7/7 London bombings (bring in the Islamic Reformation, 8 August). Rushdie is a master of timing. At a time when muslim are given to deep introspection, that “our own children” had perpetrated the bombings in the words of the Sir Iqbal Sacranie, head of the Muslim Council of Britain, the author of the Satanic Verses dons his uniforms for the new wave Islamic Reformation. To Rushdie, “traditional Islam is a broad church that certainly includes muslims of tolerant, civilized men and women but also encompasses many whose views on women’s rights are antediluvian, who think of homosexuality as ungodly, who have little time for real freedom of expression, who routinely expresses anti-semitic view … what is needed is a move beyond tradition – nothing less than a reform movement to bring the core concepts of Islam into the modern age, a Muslim Reformation to combat not only the jihadist ideologues but also the dusty, stifling seminaries of the traditionalists …”. This has uncanny resonance with the calls of Irshad Manji who anchors Canada’s QueerTelevision and hailed by the western media as “Muslim lesbian intellectual” with the publication of her book the Trouble with Islam, “If ever there was a moment for an Islamic Reformation, it is now. For the love of God, what are we doing about it?” If “Islamic Reformation” has too close an association with Christianity, “Liberal Islam” is more recognizable to muslims as the agenda to empty Islam of its ethical, moral and juristic tradition and bringing it in line with “modernity”.

The problem of racial bigotry, disgust of homosexuality and unmodern views on women exist in every society, not least within america’s bible belt which has thrown up the occasional bombers and a senator who recently called for the assassination of a democratically elected president of a sovereign state. Do they now need a Re-Reformation? But what really drives today’s fashionable question of “why has Islam not undergone a Reformation like Christianity and Judaism?” is “Islamic terrorism”. This is a question asked by both well-intentioned non muslims and those impatient at muslims’ resistance to post-christian consumerist materialism of the west.

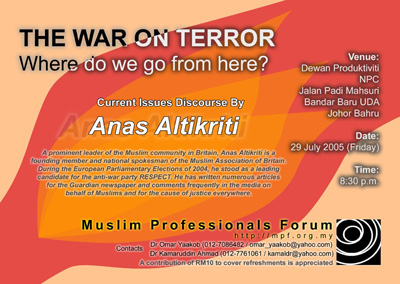

We acknowledge that terrorism as a political weapon of the weak is largely a muslim problem today. But what muslims really need is a reformation of their politics, not their religion – a political reformation that will seek to establish distributive justice, genuine representation, respect of fundamental human rights, good governance, people oriented policies and serious efforts at poverty eradication. Since September 11 volumes have been written by experts on the roots of muslim terrorism. Denying Al-Qaeda new recruits is not such a difficult thing. Just simply stop propping up brutal dictators in the middle east and let the people choose their own governments. Secondly stop subsidizing economically, military and politically the state of Israel and restore justice to the Palestinian, and thirdly end the occupation of Iraq, all this at no cost to american tax-payers. Bringing “the core concepts of Islam into the modern age” as Rushdie wishes us to do is a mischievous opportunism that exploits the pervasive fear and distrust, quite a lot of it is manufactured, towards a people whose values may not accord with modern liberalism.

With secularization, modern western education and penetration of western culture into traditional muslim societies, the proponents of Islamic Reformation or liberal Islam attempt to deconstruct at doctrinal level the scholarly consensus on Islam’s traditional pillars of theology, jurisprudence and spirituality, and at praxis level to dilute muslims’ observance of Islam’s rituals and practices, and questioning its moral teachings whenever they appear incongruous with the values of modernity. Naturally the most vexing issues are the ones where Islamic norms and teachings are most jarring to modernism’s eyes such as the question of the rights women, sexuality and Islam’s moral strictures. This have been the vehicle by liberal Islam to effect a complete break from the stifling weight of tradition and the dogmas of orthodoxy which have always been blamed for muslim decline. The panacea is appropriation by all and sundry the right to “ijtihad”, to re-interpret religion, to remould it nearer to the heart’s desire.

It must have been a source of wonder to non-muslim observers why is it that the propents of “liberal” or “progressive” Islam have remained on the fringes, unable to penetrate the Islamic mainstream despite its noble themes centred around such liberal values as human rights, gender equality, human progress, and freeing society from the moral strictures of an era long gone. Why are muslims so resistant to positive changes?

First, despite their pretensions to liberalism, the main concern of liberal Islam appears to be to graft western norms in matters of sexuality, morality and women issues onto a largely conservative muslim society masquerading as “fundamental freedoms”. Though these are problems that need to addressed, they are relatively peripheral issues. Our central concerns are really the widening income gap, urban poverty, stresses on family life imposed by the modern exploitative economy, and in may muslim countries, the suppression of those truly fundamental liberties of expression, thought and political association which are the cornerstone of a genuinely representational, democratic polity. What is really promoted in the end is not so much a political liberalism whose emphasis on fundamental rights muslims have no difficulty identifying with, but rather a moral libertinism of post-christian west. Secondly, and this is perhaps a far more serious concern, liberal Islam’s stubborn insistence on the right to “ijtihad” or re-interpretation of Islam is based on the highly persuasive argument that religious truths should not be the monopoly of traditional scholars, who, stuck in the cobweb of stagnant traditions, have spectacularly failed in making muslims conform to the liberating values of modernity. This strikes at the heart of traditional Islamic scholarship with its strict emphasis on hierarchy of knowledge and respect for specialization in various branches of Islamic sciences of theology, jurisprudence and spirituality. What muslims see in this “ijtihad” by proponents of liberal Islam who have no formal pre-requisites of Islamic knowledge is the destruction of a major pillar of Islam, the sunna, upon which rests Islamic praxis (the Shariat), and the selective rejection of Quranic verses that contradict modernity’s latest fashionable ideas. What mainstream muslims see in this whimsical “ijtihad” is a confusion and chaos that will lead to the dilution and ultimately the destruction of Islam itself.

However since “the war on terror”, we have seen liberal Islam or Islamic Reformation improve its fortunes. The neo-cons’ “war on terror” is using liberal Islam to do its bidding in the muslim world. They are natural allies as both have a healthy dose of disdain for people who prefer to live their lives as muslims rather than succumb to western culture, and not so much that all 1.3 billion of them are potential terrorists. On the eve of the US invasion of Iraq, Paul Wolfowitz confided that “we need an Islamic Reformation”. One year later, another prominent neo-conservative, Daniel Pipes of the Middle East Forum (MEF) declared that the ultimate goal of the war on terror had to be Islam’s modernization or as he put it “religion-building”. Pipes was then seeking funding for a new organization, tentatively named the Islamic Progress Institute (from AntiWar.Com, “Neo Cons Seek Islamic Reformation” by Jim Lobe). One of the people whom Pipes has invested hope in this Reformation project is Irshad Manji whom he calls a “moderate” muslim. It is strange that in a few short years what is generally understood as “moderate” muslim has shifted from that of a fully practicing muslim who sees terrorism as against the teachings of his/her religion and shares the humanistic universal values with the rest of the world, to someone whose idea of reforming Islam is to make it conform to western sentiments and norms who argues that Islam’s disapproval of homosexuality is the result of a faulty exegesis of scriptures. That makes all of us extremists except Rushdie, Manji and propents of liberal Islam.

Thus the thrust of the neo-cons think-tanks like Pipes’ MEF and the Rand Corporation is to support and give prominence to individuals and groups that range from Irshad Manji and the Al Fatiha Foundation in the west to intellectuals, scholars and NGOs that seek to propagate liberal Islam in muslim countries. But the choice a trojan horse in Salman Rushdie from whom muslims are still smarting from his denigration of their Prophet, Irshad Manji and a whole host of liberal Islam advocates in the muslim world is too unsubtle and crude that mainstream muslims have no trouble recognizing instantly that “Islamic Reformation” is an attempt to neuter Islam.

This is not to say that muslims have never thought about “reforms”. Given the state of muslims in the 20th century where poverty, political despotism, corruption, enfeebleness, economic backwardness are the norm – we are often given to nostalgic sentimentalizing of our glorious civilization before the ascending of europe. On top of that anti-semitism, dogmatism, sexism and paranoia in rife in Islamic societies today. Although this is not exclusively a muslim problem, it is reasonable to accept that this is more pronounced among muslims for the main reason that it has been on the losing side of a long conflict with the west. Many thinking muslims agree that we need to make ourselves feel at ease with modernity and awaken from our centuries of stupor, stagnation and dependency. Very few disagree on the need to master modern knowledge and the sciences, modern administration and polity, and learn to live and interact with other people as part of one humanity in all its diversity. This need for reforms started to be felt in late 19th century when large swathes of the muslim world came under western domination through colonialism and the progressive defeat of the Ottoman empire. There is a vast body of scholarly literature on these pioneering reformers of Islam – Jamaluddin Afghani, Muhammad Abduh and Rashid Rida – and the Islamic movements of the 20th century inspired by them. This genuine reformist movement aimed at taking muslim society out of stagnation and decline by creating a synthesis between modern values and systems, i.e. the positive aspects of western civilization, and Islam’s universal values. They also used the language of progress, modern knowledge, the primacy of rational thought and ijtihad. However like today’s proponents of Liberal Islam on a mission of Islamic Reformation, there was also the general tendency of doing away with accumulated tradition of jurisprudence of the 4 legal schools (madzahib), theology (kalam) and spirituality (tasawwuf), if not laying the blame of muslim decline on these “sclerotic” traditions.

But history has not been kind to this reformist project through both internal and external factors, not least western support of secular muslim dictators in the middle-east. This has been charted well by Olivier Roy in his well-known work l’échèc de l’Islam politique (the failure of political Islam). In this insightful work, Roy examined the metamorphosis in the reformist movement in its struggle for a social, political and economic revival of the muslim world led by modern educated professionals and technocrats who nevertheless remained pious muslims, to what he calls “neo-fundamentalism”, a literalist and rigid interpretation of scriptures that seek to bring muslim society back to an idealized past.

Increasingly, many commentators, muslims and non muslims, like Roy and Benjamin Barber in “Jihad vs Ms. World”, have argued that it is this militant neo-fundamentalism, itself partly a product of cold war proxy politics in Afghanistan, combined with romantic individualism of the west, that has created the modern phenomenon of Islamic terrorism. This is the unintended, mutant outcome of the initial impetus for Islamic revival or reform. Caught in an impasse between a rigid literalist interpretation of Islam that is vehemently anti-west in tone and a hyperliberal one that seeks to remould Islam to the mores and ethics of post-christian west – both driven by self-styled “ijtihads” that repudiate the consensus that has been built over centuries of classical Islamic scholarly tradition – muslims are now re-examining “traditional Islam” . There is a growing literature that is beginning to have an influence on modern educated muslims on traditional wisdom and texts, especially the extensive corpus of Al Ghazali that covers theology, spirituality, Islamic praxis and morality. Rather than sclerotic, stagnant traditions, classical Islam was alive with theological and jurisprudential debates. In “bombing without moonlight” (Islamica, Spring 2005), Abdal Hakim Murad wrote, “it was on the basis of this hospitable caution that non-Qutbian Sunnism engaged with modernity. Reading the fatwa of great twentieth century jurists such as Yusuf Al Dajawi, Abd Al-Halim Mahmud and Subhi Mahassani, one is reminded of the Arabic proverb cited on motorway signs in Saudi Arabia : there is safety in reducing speed. Far from committing a pacifist betrayal, the normative Sunni institutions were behaving in an entirely classical way. Sunni piety appears as conciliatory, cautions and disciplined, seeking to identify the positive as well as the negative features of the new global culture”. That elusive enlightenment we have been seeking for more than a century is not likely going to be through an Islamic Reformation of either the anti-west literalist interpretation or a hyperliberal self-loathing one born of an inferiority complex to the west, but a return to the wisdom, beauty and richness of tradition.

Dr. Mazeni Alwi